Despite the appeal and convenience that artificial intelligence has brought to the financial industry, there is still evidence of inherent bias in its algorithms that slow, and even expel, loan approvals for minority cohorts. A way to polish this imperfect system is Fairplay, an AI fairness solution for any company that uses algorithms to “make high stakes decisions about people’s lives.”

Coining itself as the first “Fairness-as-a-Service” platform, the fintech revealed Monday it raised $4.5 million in seed investment funding led by Third Prime Capital to help businesses mitigate discriminations in their technology.

Other investors in the round included FinVC, TTV, Financial Venture Studio, Amara and Nevcaut Ventures.

“Just as we built search infrastructure and payments infrastructure for the Internet, so must we build fairness infrastructure for the Internet,” says FairPlay Founder & CEO Kareem Saleh.

FairPlay is going to market in financial services with two APIs. The first API provides Fairness Analysis, analyzing a lending model’s inputs, outputs and outcomes to provide insights into whether disparities exist and for which protected groups.

The second API, called Second Look, re-underwrites declined loan applications using its AI fairness techniques that are designed to do a better job of assessing borrowers from underserved groups. These techniques can determine whether declined applicants resemble “good” borrowers in ways that the primary algorithm did not strongly consider. The result is that more applicants of color, women and other historically disadvantaged people are approved.

“What we find is that one out of three, or one out of four, of those declines on a loan was a false negative and that those individuals would have performed as well as the riskiest borrowers that lender is approving,” Saleh told FinLedger.

For Saleh, it was this exclusionary lending that shaped his career. In an interview, the CEO explained how his parents – North African immigrants – came to the states in need of a small business loan. At the time, not a single bank in Chicago would lend to them. These tribulations made Saleh reflect on the systems created to underwrite inherently hard to score borrowers.

How do you underwrite under conditions of deep uncertainty, Saleh asked. After digging in to the underwriting systems of major financial institutions, Saleh found that even at commanding heights there were rudimentary disparities.

“In the last several years, we’ve seen the emergence of these new AI fairness techniques that not only allow you to identify bias, but also to remediate it,” Saleh said. “It was really around the time of George Floyd’s death last year that we decided we had to build a team of people to see if we could do something about this.”

That team included John Merrill, Fairplay’s CTO who spent a combined 15 years at Google and Microsoft implementing and engineering AI systems.

So how does a company measure fairness?

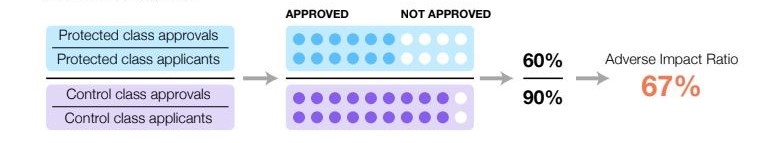

Saleh explained they have ultimately settled on the Adverse Impact Ratio because of its standard use by judicial courts and regulators. The ratio is a measure of demographic parity and is the first step to gauging whether members of a protected class get a positive outcome – being approved for a loan – as often as a control group.

The software answers 5 key questions for customers:

- Is my algorithm biased?

- If so, why?

- Could it be fairer?

- What is the economic impact of being fairer?

- Did we give our declines a second look to see if they resemble good applicants on dimensions we haven’t heavily considered?

Fairness in mortgage lending

On top of its latest APIs, Fairplay also announced the launch of its Mortgage Fairness Monitor, a data-driven map of how fair the mortgage market is to Black Americans, women and Hispanic Americans based on a review of 20 major metropolitan areas in the U.S.

The tool began as an internal tech source when Saleh needed to meet with a lender and wanted to pull all the HMDA data surrounding it.

“I wanted to know if they’re fair or not and I would get this huge HMDA spreadsheet that I couldn’t make heads or tails of,” Saleh explained. “After three or four meetings like this I asked the team to just plot it on a map for me. So we scraped the whole HMDA database for 2020 and 2019 and 2018 as an internal tool to understand what is the state of mortgage fairness, by geography and by financial institution.”

For Saleh’s team, the data showed large disparities between lenders – though they wouldn’t disclose who – and that the data is more nuanced than just is this a big or small institution.

“We are still trying to understand the fault lines,” Saleh said. “What does make a difference, however, is how modern are their underwriting systems and techniques, and how are they marketing to certain communities.”

Fairplay’s data came back revealing and reiterating homeownership themes the industry has been echoing for years.

A 2021 investigation by The Markup found lenders were more likely to deny home loans to people of color than to white people with similar financial characteristics. Specifically, 80% of Black applicants are more likely to be rejected, along with 40% of Latino applicants, and 70% of Native American applicants are likely to be denied.

A study from the National Bureau of Economic Research noted that “if lenders were to discriminate in the accept/reject decision, it would imply that money is left on the table. …(s)uch unprofitable discrimination must reflect a human bias by loan officers,” Forbes reported.

“FairPlay is turning fairness into a business advantage, allowing our users to de-bias digital decisions in real time and prove to their customers, regulators and the public that they’re taking strong steps to be fair. In short, FairPlay makes fairness pay,” Saleh added.